FINDING HOME AWAY FROM HOME: UKRAINIAN REFUGEES IN THE USA

As the Russian Invasion of Ukraine unfolded in a chaotic and shocking fashion in February of 2022, television and computer screens across the globe shared a harrowing visual, millions of Ukrainians and their families scrambling to escape the carnage of a war that descended suddenly on their home. Rail stations, busses, border crossings, airports, and subway tunnels were crowded with civilians who overnight had to pack all of their belongings and flee their homeland as the horrors of war descended upon them. The invasion sparked one of the worst refugee crises in Europe since World War 2 as Ukrainians en masse fled. Many took shelter in neighboring countries such as Poland or Romania, others however found themselves on the other side of the ocean, a continent away.

Hamtramck and Warren, Michigan are two cities within the Detroit Metropolitan Area and have always been a hot spot for newly arrived immigrants and refugees since the late 1800s. A Ukrainian diaspora has thrived in the Detroit Metropolitan area since the 1930s when the Holodomore and pogroms forced many eastern Europeans to flee their native homelands. Nearly a hundred years later, the newest members of the Ukrainian Diaspora, arrived much in the same manner, confused, unsure of the future, and in need of assistance from fellow countrymen who made the journey before.

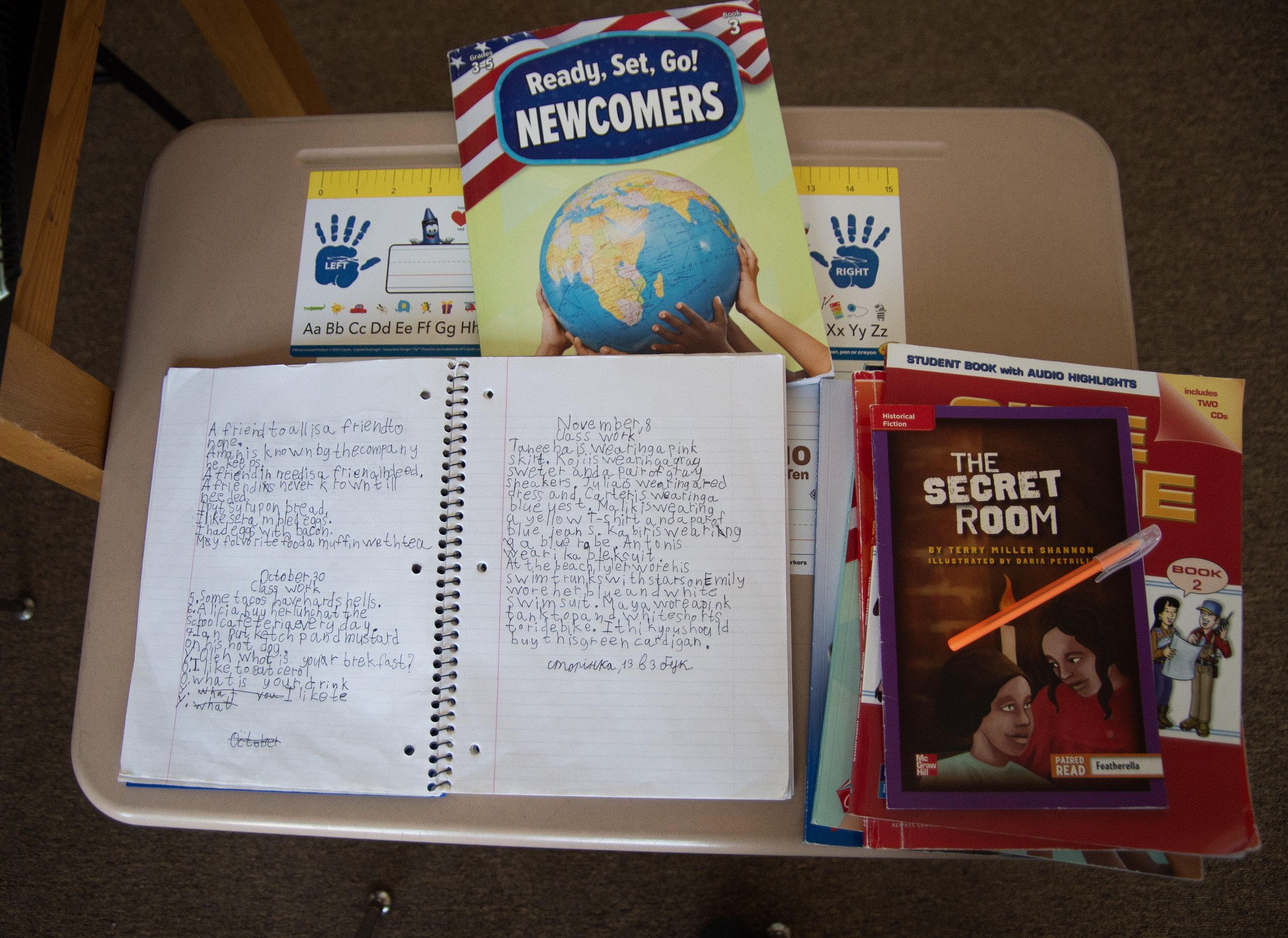

Many of those who find themselves in a new and unfamiliar city are children and their families. In Hamtramck, the Caniff Liberty Academy School specializes in educating and providing resources to children and families who end up far from their homeland due to war and famine. In the months following the outbreak of full-scale war in Ukraine, the school saw a massive uptick in Ukrainian students, newly arrived to the US, being enrolled, many with little to no English speaking ability, and others bearing the symptoms associated with trauma.

“We had a routine fire drill one day, and some of the Ukrainian students began shaking and crying, absolutely terrified that we were going to be bombed.” Mitra Entcheva recalls.

Ms. Entcheva, a second-grade teacher at the school, was one of the only staff members who could communicate with the newly arrived students from Ukraine. A native of Bulgaria, she spoke Russian which many of the newly arrived Ukrainian students could understand, however with the massive influx of Russian and Ukrainian-speaking students the school was forced to hire additional help.

Iulilia Surzhyk is one of the new staff members of the school and she teaches the newly arrived Ukrainian students English in a separate classroom. She leads her students through their lessons, speaking in the authoritative yet gentle tone many of her students are used to in their home country. Iulilia herself a refugee from Eastern Europe, and a prominent member of the Ukrainian community of Detroit, understands the culture shock and difficulties with sudden change.

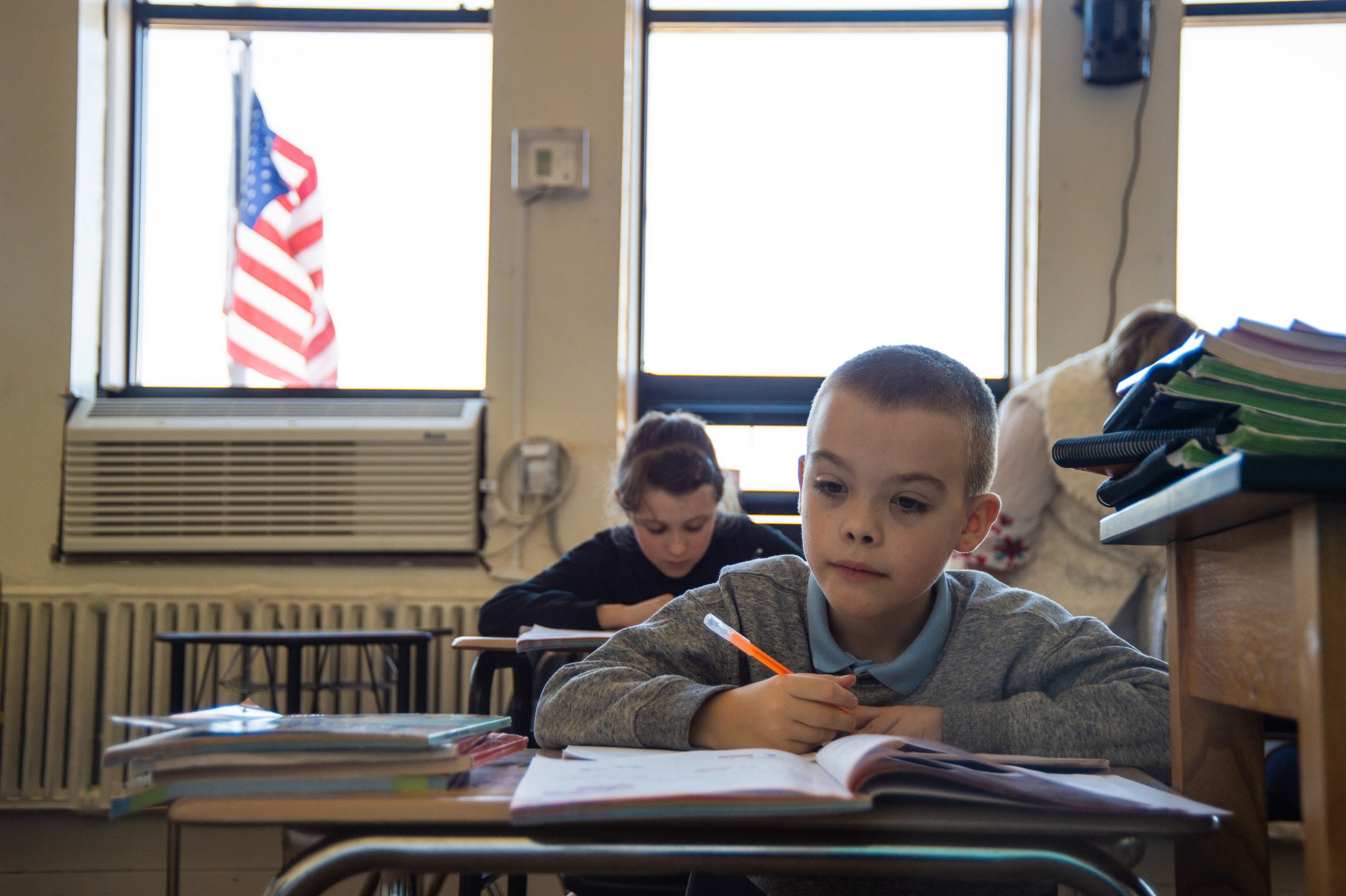

“For many of these students, they have difficulty because they are actually a year ahead of where they are being placed in school now. The language barrier is the biggest obstacle, in all other subjects they are very advanced and some of them find classes boring, they are having to relearn what they already learned back home.” She says in between classes.

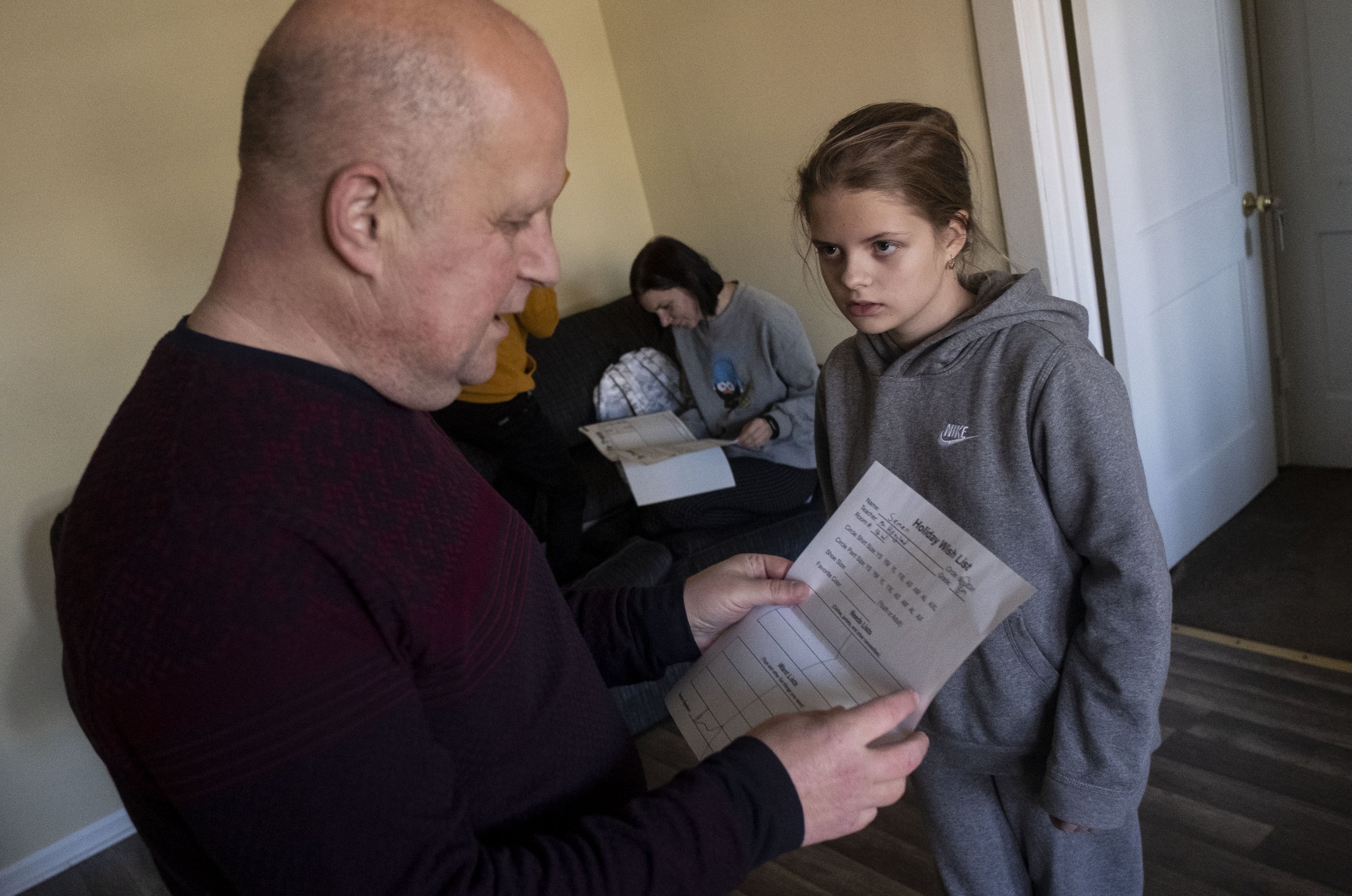

For 11-year-old Sofia, and 10-year-old Semen Valychko this is painfully clear. The two came to Hamtramck with their parents Dmytro and Maria in November 2022. The family had opted to try and stick it out in their hometown in Ternopil Oblast as long as they could, however, when Russian missiles landed near their village, they decided it was time to leave.

In Ukraine Sofia and Semen competed in youth chess tournaments, and were advanced in their studies, now because of the differences in the education system and a language barrier they both find themselves relearning much of what they already studied in school. Their parents follow a similar path as well, where back at home they were professionals in their career, but they now spend the hours from when their children go to school to when they return searching for jobs and often checking the news for the latest on the war.

“For now this is only temporary, we want our children to grow up in Ukraine, in our home, so we will do what we must, but we will return.” Maria expresses as they drive their children to school, rows of suburban homes pass by as she watches.

“When we can return, we will.” Dmytro adds as he pulls the car up to the school.